Once a dissemination strategy has been determined, the initial report needs to be written. Almost all social, business health and medical research would require a report of the research and outcomes. This report may not be the main dissemination instrument but will be the basis of all subsequent publication. The report may be designed for internal use or a report to funders, which may not be otherwise published; in which case the aim may be to produce a series of journal articles based on the report. On the other hand, the report may be the primary publication, with a view to spinning off items through other forms, such as newspaper and journal articles and conference presentations.

Top

11.2.1 Readability

So, in any event, the research report is an important document. It is the culmination of a lot of work. It needs to clearly show what has been learned from the research undertaking. In many respects, the research will be judged on the basis of the report produced. So, make it interesting and readable. A readable report is one with a 'plot'. Ideally, tell a story to the reader. That does not mean that it is fictitious; it means that the report writer should not expect the reader to do the work of making sense of the data. What the reader is being told should be straightforward to follow, convincing and interesting. Just because it is academic does not mean it has to be boring.

A readable report is one that has a central theme or 'angle'. The report should take the reader through the aims, objectives, method, data and conclusions in the same way that you would expect if you were reading an article or book, although there will inevitably more technical material in a research report than is likely, for example, in a book.

There should be a reasoned argument and the data should relate to the argument. Do not simply pile in table after table, diagram after diagram, quote after quote without any comment or any attempt to relate them to the aims of the survey. That is a surefire way to make a report boring and ultimately unreadable. More importantly, remember that data does not speak for itself. Statistical data, for example, can be interpreted in different ways according to the theoretical perspective adopted by the interpreter, the presuppositions about the data and the techniques used to do the analysis.

Raphael Silberzahn and Eric Uhlmann (2015) illustrated this. They argued that statistical analysis of data undertaken by a research team (or single scientist) risks being misleading because the researchers have certain preconceptions from their research role that makes it difficult for them to step back and reassess the data. They stated that:

researchers take on multiple roles: as inventors who create ideas and hypotheses; as optimistic analysts who scrutinize the data in search of confirmation; and as devil's advocates who try different approaches to reveal flaws in the findings. The very team that invested time and effort in confirmation should subsequently try to make their hard-sought discovery disappear.

Silberzahn and Uhlmann argued that the role of devil's advocate should not be undertaken by the researchers themselves but should be played by other research teams.

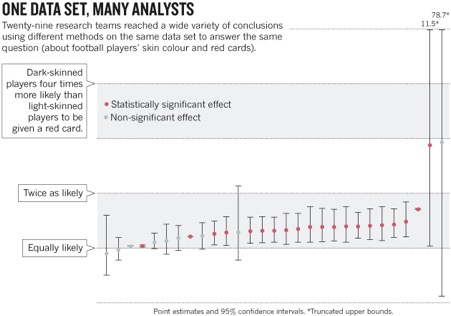

They conducted a simple experiment to add weight to their point. They recruited 29 teams of researchers and asked them to answer the same research question with the same data set. The data analysed were taken from four major association football leagues. 'It included referee calls, counts of how often referees encountered each player, and player demographics including team position, height and weight. It also included a rating of players' skin colour.' The different teams approached the data with a wide array of analytical techniques, ranging from Bayesian clustering to logistic regression and linear modelling. Some adapted the data, for example, some teams avoided double-counting games with the same referee, while others used the raw data.

Of the 29 teams, 20 found a statistically significant correlation between skin colour and red cards. The median result was that dark-skinned players were 1.3 times more likely than light-skinned players to receive red cards. But findings varied enormously, from a slight (and non-significant) tendency for referees to give more red cards to light-skinned players to a strong trend of giving more red cards to dark-skinned players (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Results of data analysis experiment: Silberzahn and Uhlmann (2015)

Following initial analysis, Silberzahn and Uhlmann followed up with rounds of peer feedback, technique refinement and joint discussion. Some approaches were deemed less defensible than others, but no consensus emerged on a single, best approach. After reviewing each other's reports, most team leaders concluded that a correlation between a player having darker skin and the tendency to be given a red card was present in the data. However, the overall group consensus 'was much more tentative than expected from a single-team analysis'.

Top

However, there are still elements of such diverse reports that remain fairly consistent. Table 11.1 offers a generic suggestion for how to structure a research report. It is not set in stone and should be used flexibly to suit the research undertaken.

There is no requirement, either, that you write up the sections in the order shown in Table 11.1. You might find it easier to write the method section (8) at the beginning, or set out your broad findings (9) early on; although an early draft of your aims and intentions (1) will provide you a framework within which to locate all the other parts.

In some situations, the components of the research report are predetermined, for example, students may be given a template for a project report, or funders may provide the headings for a research report. In those circumstances write the report to fit such templates. Where you have freedom, using the suggested structure in Table 11.1 will help you really understand your research and be able to promote it effectively.

Table 11.1 Suggested structure for a research report

1 |

Aims: |

What the research set out to find out. |

2 |

Social context |

Explain the interest in this subject and the background to the study. |

3 |

Academic context |

Outline other research work has been done in the area, what is the current knowledge of the subject and how does this relates to the research aims. |

4 |

Epistemology |

Explain the underlying approach to the research? (For example, is it an attempt to prove or disprove a thesis? An interpretation of an event? A critique of a social system? In short, make clear the epistemological presuppositions. |

5 |

Methodology |

Describe the that approach has been adopted for data collection and examination and why. Show how the proposed method relates to the epistemology. |

6 |

Operationalisation |

Where appropriate, explain how key concepts referred to in your aims are operationalised. |

7 |

Hypotheses/lines of enquiry |

State the objectives of the study (including the hypotheses and sub-hypotheses where appropriate) or indicate what specific aspects of research aim are being explored in the research. |

8 |

Method/techniques |

Explain in some detail how the information/data was collected, or if secondary data where it was sourced; and the problems encountered. |

9 |

Findings |

Present the findings of the research. If you undertook survey research, what you found out about each hypothesis. Or, if you did an ethnographic study or a historical analysis, what themes emerged from your data? Relate these to your aims. |

10 |

Theoretical relevance |

Discuss the significance of the results and how they relate to other key findings in the area. |

11 |

Summary |

Overall, sum up what has the research revealed. |

12 |

Recommendations |

What recommendations, if any, can be made based on the research. |

13 |

Conclusion |

Explore the implications of the research for theory, practice and methodology. |

1. Aims: Set out the aims of the research as clearly and concisely as possible. Use the aims to structure the report. Outline what the 'angle' (the main line of argument) and use it as a theme running through the report to give the exploration of the data a focus.

For example, the Work Experience report (Harvey et al., 1998, p. 2) explained:

The research reported here explores what can be done to increase the opportunities for undergraduates to gain work experience and how the learning from these experiences can be maximised. The project has aimed to specify the range and variety of work experience for undergraduates.

Top

2. Social context: Explain the reasons for undertaking the research and provide a context that situates the approach taken.

For example, the Work Experience report (Harvey et al., 1998, p. 1) states:

Work experience has re-emerged as a significant issue in higher education and the research reported here attempts to identify strategies to increase work-experience opportunities and to ensure that these opportunities offer a meaningful experience — that they are learning opportunities. There is a difference, therefore, between 'working' and undertaking a period of work experience. 'Work experience' is defined as a period of work that is designed to encourage reflection on the experience and to identify the learning that comes from working.

This context comes before the presentation of the 'Aims' in the published report, which illustrates the flexibility of the suggested scheme. If the report reads better with context before aims, then write it that way.

In the CASE STUDY Attitudes towards homosexuality, the research was undertaken in the context of the growing concern about AIDS. In particular, in the light of the 'moral panic' surrounding gays and lesbians towards the end of the 1980s, the political initiative of the Conservative Government in undermining Labour local authorities was linked to the broader context of right-wing moralism and family values.

3. Academic context: This frames the research by exploring what is already known in the area, assessing previous results, critiquing what has gone before, revealing gaps in knowledge or questioning published results and taken-for-granted assumptions. As well as situating the research, it also provides the reader with a good introduction to the topic.

This section is often referred to as the literature review. The important thing is to make the review pertinent to the report by relating the literature being reviewed to the aims of the study. Avoid just a listing and description of previous studies without indicating how they relate to the research being undertaken.

Note that previous research may be published in journals or books or on research centre websites. There is also a lot of research that is not so easily accessible: conference presentations, for example, which are often work in progress, along with working papers, doctoral theses and private reports, these may all be useful sources but fall into what is generally referred to as grey literature. This is material that has been written essentially for limited consumption and not openly published. Grey literature can be rewarding but is traditionally more difficult to find, although the Internet now makes it more accessible than it used to be.

In rare circumstances, if the research is in a novel or unusual area, there may be little or no existing research to review.

The first draft of the literature review can be written before the research is completed. Indeed, it is often useful to do that to ensure the researcher has a good grasp of what has and has not been already researched and the outcomes of that work. Writing a critical review of the existing literature in the research area, provides the academic context for the research and helps develop and refine the argument as the research progresses and can help sharpen the focus on the research questions.

It is important to remember that critiquing others' research is not about being negative or deriding their work but rather presenting a well thought out evaluation of the argument presented, the methodology employed, the interpretation of the data and the context in which they presented their findings in relation to previous studies. The assessment may be positive, negative or neutral.

Top

4. Epistemology: Essentially, this involves a clear statement of the underlying presuppositions. To think through and explicate the epistemological position is useful both to the researcher in sharpening the report, making it clear where the research is or is not coming from. This also helps readers, giving them a clear insight into the research orientation.

The epistemology section is often ignored, excluded or skated over, or briefly mentioned in the methodology section, to which it relates.

For example, the Work Experience report (Harvey et al., 1998, p. 4) glossed over the epistemology, locating the following under 'methodology', inferring, rather than being explicit about, a critical approach beyond the basic analysis of the qualitative data:

The research process involved the following stages:

- an exploratory-descriptive stage identifying current practice and terminology;

- an analytic stage exploring examples of work-based learning in practice and examining how it develops the skills and knowledge of students;

- a critical-reflective stage exploring stakeholder views of the role of work-based learning and devising an approach to assess the impact of work-based learning at a personal, organisational and system level.

When writing the report the epistemology section does not need to specify any particular 'ism', rather it should make clear the thinking behind the approach adopted. For example, in her study Soap Opera and Women's Talk, Mary Brown (1994, p. xi) took a feminist overview but fundamentally derived her analysis from immersion in the subject:

Mine is an ethnographic study in which I am a member of the group, a fan, and also the researcher. Ethnography…has come under criticism for projecting the stance of the researcher through the voices of the subjects. This is always a danger in ethnographic work, but no more so now than in the past. I feel that, to pay attention to the specific practices of participants in fanship networks and other television spectator practices, ethnographic work is necessary and value. Otherwise audience theory is based on an audience of one, the author of that theory.

Here Brown is specifying what might be referred to as a phenomenological or interpretive approach, although explaining it by reference to ethnography and being a member of a group. In addition, she refers to the underpinning approach: audience research.

Others are blunt in their assertion. Dave Harker (1980) referred to his analysis of pop music as a Marxists dialectical musicology; and Howard Becker et al. (1961) Boys in White is an interactionist ethnography of medical students.

Sally Westwood (1984, pp. 5–6), in her all day every day study of female factory workers is explicit that: both capitalism and patriarchy affect women's subordination. She does not see capitalism or patriarchy as wholly autonomous nor reducible one to the other. For her, patriarchy and mode of production are 'simultaneously one world and two, relatively autonomous parts of a whole which has to be fought on both fronts'. She sees the lives of her subjects as 'encompassed by patriarchal relations, which are part of "patriarchal capitalism"'.

5. Methodology: This section should explain the methodological approach as opposed to the particular method(s) adopted (see Section 1.3). (Precise details of the method(s) used and problems encountered come later in the report (Item 8 in Table 11.1). The methodology sets out the overall perspective and how the proposed research reflects the epistemological stance.

The methodology explains how the approach selected is appropriate given the purposes or aims of the research? It demonstrates how the proposed methods for collecting evidence are compatible with the epistemological assumptions. Do they, for example, provide a basis for causal explanation, or will they generate the kind of data for a rich interpretation, or are they able to contextualise the research to enable a critical approach or an understanding of underlying ideology? In short, methodology is about the whole approach to an area of research.

For example, in their study of migrant and non-migrant networks, Parvati Raghuram et al. (2010, pp. 629–30) justified their approach and explained the methodology of the study, which drew on oral histories of geriatricians (who played an important role in the establishment of the discipline during the second half of the 20th century) to explore the importance and power of non-migrant networks in influencing migrant labour market opportunities in the United Kingdom medical labour market.

The choice of oral history as a method in migration studies is well attested. It offers the possibility of locating the migration experience within the longer trajectory of a life history, contextualizing migration as one of many events that shapes individual lives. It is produced in a dialogue which encourage narration and reflection and thus provides evidence of subjective lived experiences (Perks and Thomson, 2006; Thompson, 2000). Comparing two different datasets has produced its own richness, undermining the alterity that is ascribed to migrant networks but also exposing the partial fluidity of the boundaries of elite networks.

The oral history interviews have been supplemented by archival research. The archives of the Department of Health, the British Geriatric Society, the British Medical Association, the Royal College of Physicians, the Royal Society of Medicine and the papers of organizations such as the Overseas Doctors Association have all been consulted to provide an understanding of the issues facing doctors working in the specialty in the second half of the 20th century.

Make sure the methodology section is set out clearly. This is important for the reader; although a clear methodology also helps the researcher orient and focus the work.

Top

6. Operationalisation: Operationalisation is the specification of how a theoretical concept is turned into a measurable variable. The report should set out how key concepts are operationalised for data collection purposes. See Section 2.2.2

This is particularly important in a positivist study, using social surveys for example, where the operational definition of variables is key in allowing readers to make sense of the data and results. Inevitably, the questions will arise, 'who is included in…?', 'how did you determine different levels of…?', and so on? (Section 8.3.5 looks at operationalisation as part of social surveys in more detail.)

Phenomenological and critical studies are less likely to have clear operationalisations for measurement of variable at the outset and operational definitions often emerge from the research and then may be indicated retrospectively in the report. What, for example, counts as 'deviant behaviour' in a specific study may only emerge from immersion in the research setting. Similarly, what constitutes 'dominant ideology' may emerge as an understanding as a result of the critique. Thus, in critical and phenomenological studies there may be no section in the report on operationalisation, as the whole study may revolve around discussing the very nature of the main concepts in the study.

An example of operationalisation is CASE STUDY Operationalising Poverty, which reviewed how Peter Townsend (1979) operationalised poverty.

Further, in their study of how social mobility relates to educational field of study, Herman G. van de Werfhorst and Ruud Luijkx (2010, p. 710) operationalised their variables as follows:

We distinguish the following birth cohorts (k): 1919–1930; 1931–1941; 1942–1952; 1953–1963; 1964–1975.

Social class and education are both measured in an aggregate and a disaggregate way. In an aggregated way commonly used to study the origin–education relationship, social origin class (l) corresponds to the eight-class version of the Erikson and Goldthorpe class schema (higher service class I, lower service class II, routine non-manual III, self-employed with no or few employees IVab, farmers IVc, skilled manual working class V/VI, unskilled manual working class VIIa, farm laborers VIIb).2 Father's class refers to the situation when the respondent (child) was around 15 years old. Education is, in its aggregate measure, operationalized in seven levels of schooling (m): primary, lower vocational (known as LBO/VBO); lower general (MAVO); higher general (HAVO/VWO); intermediate vocational (MBO); vocational college (HBO); and university.

Disaggregated, social origin (i) and education (j) are both operationalized in 24-category variables. This disaggregation was done within the aggregate groups, on the basis of the field of study (in education) and in terms of the field of occupation (in origin). Given the volume of the data we had to collapse some fields of study into one. In Table 1 the two variables are shown (summed over cohort), as well as the contingency table cross-classifying both.3 [Further details were given in notes 2 and 3, not included.]

Top

7. Hypotheses or lines of enquiry: This section of the report specifies the hypotheses that the research is testing. The research aim may have a series of objectives, which have become constructed as testable hypotheses. Positivist methodology (using surveys and questionnaires) will have this as a matter of course and the hypotheses under scrutiny should be set out in the report.

For example, Hilde Coffé and Benny Geys (2008, p. 363), in their study of how social networks bridge social boundaries, stated:

we test the hypothesis that experiences in cross-cutting or bridging associations have greater effects on democratic and social attitudes than memberships in closed or bonding associations.

Johannes Han-Yin Chang (2010) specified two hypotheses in a study of the values of Singapore's youth and their parents:

The following predictions can be derived from the scheme:

(1) If Inglehart's view on differential social conditioning is correct, it therefore follows that Singapore youth place more emphasis on values in favor of self-realization/self-expression and pleasure-seeking, and less emphasis on values in favor of religious commitment, conformity and collective orientation as compared with their parents.

(2) If Inglehart's view on differential social conditioning is correct, it therefore follows that people with an upper-class and upper middle-class background

place more emphasis on values in favor of self-realization/self-expression and pleasure seeking, and less emphasis on values in favor of religious commitment, conformity and collective orientation as compared with lower-class people.

Both hypotheses (predictions) are supported [as the author goes on to demonstrate].

In phenomenological and critical studies there may be no hypotheses for testing but the research will inevitably take a particular approach to the research area and these lines of enquiry should be stated.

For example, in their qualitative study of sectarianism in Scotland, Ross Deuchar and Chris Holligan (2010, p 14) focused on:

issues surrounding territoriality, sectarianism, social capital and youth. The roots of sectarianism in Scotland are examined against the wider historical context of British colonialism in Ireland, 'The Troubles' associated with Northern Ireland and the religious 'traditions' associated with the two largest football clubs based in Glasgow.

Top

8. Method: The method (or techniques) section provides detail of the process by which the results were obtained. It is important that this section is clear and logical and potentially easy to replicate by another researcher. When undertaking a questionnaire study, for example, the process for determining the questionnaire content should be indicated. The target sample should be identified, the means of disseminaton of the questionnaire explained and the response rate indicated. Problems that arose during this process should be set out and measures taken to overcome them or deal with the consequences explained.

Explaining the detail of a single method study is relatively easy. When a study has multiple sources of evidence, the explication of methods is more problematic, as to explain all the issues would overload the report with microscopic detail. For example, the Work Experience study (Harvey et al., 1998, p. 4), after providing the methodological overview, explained that the methods used included:

visits, telephone interviews and literature reviews to establish a picture of a vast range of work experience initiatives currently being undertaken. Initiatives explored include:

- programme-, department- or faculty-specific initiatives;

- institution-wide initiatives;

- student employment bureaux;

- initiatives between Training Enterprise Councils (TECs) and higher education institutions;

- initiatives between TECs and other local or regional organisations;

- employer organisation initiatives (e.g., ASDA, Tesco, Guinness);

- work-experience brokers (e.g., Shell STEP, Business Bridge);

- student associations (e.g., Student Industrial Society (SIS), L'Association Internationale des Étudiants en Sciences et Commerciales (AIESEC));

- national voluntary agencies (e.g., GAP, Youth for Britain, Year in Industry).

The research draws on the large body of knowledge about work-experience and work-related learning that already exists, using published books and papers on issues related to work-based learning and competencies in higher education, and relevant contributions from industry and commerce. The research has also drawn on the considerable experience of the Project Steering Group (see Acknowledgements).

There has been a re-analysis of empirical data already collected by the Centre for Research into Quality (CRQ), and the reflections of students on their STEP placements. Anonymous quotes attributed to employers and recent graduates derive from interviews undertaken as part of the field work for Graduates' Work. There has also been the collection of some new empirical data from students through a CRQ questionnaire asking sandwich placement students about their work experience.

The network study of Parvati Raghuram et al. (2010, p. 629) (mentioned under item 5) explained their methods thus:

The article draws on secondary analysis of interviews....The first data set (MJ) comprises the 72 interviews which Jefferys and colleagues carried out in 1990–1 with the founders of the geriatric specialty. Between them they cover the history of developments in the health care of older people from the late 1930s to the end of the 1980s. The second data set (South Asian Geriatricians—SAG) consists of oral history interviews with 60 South Asian overseas-trained geriatricians who have been recruited through networks of overseas doctors (British Association of Physicians of Indian Origin for example), the British Geriatrics Society (BGS) and through snowballing. These interviews cover the period from 1950 to 2000. The two datasets thus reflect slightly different, albeit overlapping, periods in the history of geriatrics—the emergence of the discipline in some centres and the adoption and adaptation of practices as they radiated out from these centres across the country. Hence, the South Asians operated in a framework where there was some national infrastructure for advancing geriatrics but faced similar issues to those interviewed by Jefferys, as up to the mid-1980s both were operating in areas that had very little local infrastructure and accorded geriatrics with little status. Both sets of interviewees developed services and progressed their careers in the context of fluctuations in the supply of and demand for geriatric doctors. However, the SAG interviewees also encountered the effects of changing immigration regulations and of living in a Britain where the meaning of race was changing—issues which influenced the habitus within which social networks operated.

The interview schedule used a life history approach, asking participants to talk about their life from childhood through to the present. All the interviews have been transcribed and deposited in the British Library.... [Further details of location of transcripts and nature of interviewees followed]

When outlining the methods avoid ambiguities. Edwin van Teijlingen (2000) was critical of the presentation of methods in a contribution in a book on health inequalities (Bartley et al., 1998). In his review, he wrote:

I particularly enjoyed the chapter by Cameron and Bernardes, 'Gender and disadvantage in health: men's health for a change', but their methods section is sloppy. Why not tell the reader how many (few?) interviews have been carried out, rather than that 'a small number of in-depth interviews' were conducted (p. 118)? Since their study focuses on prostate health, a questionnaire was sent out to men who had contacted the Prostate Help Association. However, later on the text suggests that partners of men with prostate problems were also interviewed, or that couples were interviewed together. 'One man gave up reflexology … according to his wife' (p. 125).

Top

9. Findings: Report findings in a systematic way. If, for example, the research involves undertaking a statistical analysis of answers to a questionnaire, relate the data to the hypotheses. Examine each hypothesis in turn and use the data to confirm or deny the hypothesis.

You should avoid using the 'Findings' section to list page after page of data, graphs, tables or quotations with no link to the aims and objectives of the research. Some people do this and then hope a brief summary will provide a general picture and make sense of it for the reader. There are those (mostly positivists) who insist on a rigid separation of data presentation followed by a 'discussion'; section that then somehow explains them. For example, 'The results section is not for interpreting the results in any way; that belongs strictly in the discussion section. You should aim to narrate your findings without trying to interpret or evaluate them, other than to provide a link to the discussion section.'

This frequently-used approach is extremely bad practice. Not least because it implies that somehow the data speak for themselves (see Section 11.2.1). It also implies that the interpretation is somehow self-evident. Furthermore, this approach leads to extremely boring reports with a high degree of repetition as the same material appears in findings, discussion and summary. Instead, discuss the data as you introduce it and make sure that you do so in relation to your aims. Ensure the discussion relates to your basic argument or 'angle'. This greatly increases readability of the report.

You will note that in the schema in Table 11.1, there is no 'Discussion' section. This is not an error; a well-presented readable report, with a clear line of argument (an 'angle' or 'plot') involves a 'discussion' throughout rather than consigns it to a single section.

The separation of results and discussion is not at all feasible in the case, for example, of ethnographic, historical or critical studies.

When explaining the findings be careful about being too assertive; you need to check that your results are statistically significant and that you have taken account of other factors that might have an effect before you can start talking about having 'proved' anything. Indeed, the best you can say is that your survey results make your hypotheses 'highly likely' or 'highly unlikely'. When using data to illustrate your hypotheses or to draw conclusions do so in a way that fits in with the main theme of the report.

Do not put a table or chart in without explaining what it means. The text of the report should still make sense even if the tables and charts are removed. Do not rely on the reader making sense of the tables and diagrams; provide clear explantions suitable for your target audience (see Section 11.4).

When compiling a report, it is necessary to be selective about what empirical data to include. If the data is quantitative it is very tempting to include every percentage, frequency table, crosstabulation, diagram and chart that has been used in the analysis. When reporting quantitative data, avoid presenting all the statistics in the same format. Sometimes only the key figures from a frequency table are needed and these can sometimes be included in the text, obviating the needs for a table or chart. Sometimes the whole table is needed so as to make the point more forcefully or because it is easier to make comparisons. Often, a shorter version of the table will do, or a bar chart or histogram may make the point better. Including complete crosstabulations may be necessary but sometimes reporting a single cell percentage will be sufficient. Page after page of charts, frequency tables or crosstabulations are guaranteed to deter the reader.

Similarly, with qualitative data, it is tempting to report large chunks of interviews or to pile in all the interesting quotes. Preferably, resist this. If the qualitative material does not add anything to the interpretation, then there is no point in including it. Only one or two example quotes are needed to illustrate a point made in the text. Do not include quotes preceded by a summary that says what the quote says. This leads to tedium for the reader.

Too many quotes or statistics in a report can be counter-productive because they make the report less readable.

Top

10. Theoretical relevance: the findings usually have some bearing on established theory, whether confirming it, calling it into question or suggesting reorientation of theory. The report should explain the theoretical relevance, usually referring to the aims and academic context to establish what the research has added to the body of knowledge. This may be a separate section or it may have been signalled in findings and/or is dealt with in the conclusion.

Top

11. Summary: The summary, which is optional, should simply pull out the main elements from the report as a whole, reminding the reader of aims, rehearsing process of data collection and focusing on the implication of the findings for theory and practice.

Wyatt, L.G., 2011, 'Nontraditional student engagement: increasing adult

student success and retention', Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 59(1), pp. 10–20

Under a heading of 'summary', Linda Wyatt (2011, pp. 17–18), whose study was of nontraditional student engagement, wrote:

Research indicates that a growing segment of the student population on college campuses today and for the foreseeable future will continue to be the nontraditional student. Consequently, it is imperative that institutional leaders become more effective in integrating and engaging the population of nontraditional students into the collegiate environment. This research was an examination of one institution, University of Memphis, which led to the development of a model that I consider to be a logical approach to not only encourage nontraditional student engagement on college campuses but increase the numbers of these students desirous of obtaining higher education.

Top

12 Recommendations: Recommendations tend to be directed at interventionist action rather than recommendations for theory. Not all research lends itself to making recommendations. However, if the research suggests recommendations then it is worth specifying them in a separate section.

Wyatt (2011, p. 18), listed her recommendations:

Consequently, based on the study findings the following are recommended for best practices to improve and increase nontraditional student engagement:

1. Institutions must look at what nontraditional students need at various stages of academic career (i.e., first-year, sophomore, junior, and senior year in college).

2. Institutions must provide tutoring labs and services identified specifically for students aged 25 and above staffed by tutors aged 25 and above.

3. Faculty should strive to understand and adopt their teaching methods and delivery systems to incorporate nontraditional student learning styles.

4. Counselors who understand nontraditional student needs and desires are instrumental in their integration to college life and successful degree completion. Therefore, it is important to hire and train counselors and advisors who understand nontraditional student issues and needs.

5. Institutions need to develop programs and events that would appeal to nontraditional students and include their families.

6. Increase campus communication to include improved marketing strategies targeted toward nontraditional

students. This includes Web site improvements that foster easier access to campus information and programs. 7. General education requirements imposed on all college students are particularly difficult for this population of students. Nontraditional students have been out of high school for a longer period of time and find math and science coursework difficult. Institutions must look at improvements in these course offerings to include more online coursework with tutorials, streamlining general education courses in shorter blocks of time, and reducing duplication in coursework.

13 Conclusion: The conclusion provides you with the opportunity to highlight and draw together your argument. It is a chance to recap on the important aspects of your research and to reiterate the context of your thesis or paper, demonstrating your broader understanding of the area within which you are researching. The conclusion goes beyond summary and emphasises the novel in the study, notably the impact on current understanding of the area of study.

For example, Rodanthi Tzanelli (2006, p. 945) re-examined the nature of kidnapping, a crime that had received little attention in sociological literature, and concluded:

In this article I have argued that a classification of kidnappings into political or economic may not be helpful for sociology-oriented criminological enquiry because it is not followed by an understanding of the social logic of this crime.… The exchange mechanisms of kidnapping are patterns of social conduct, webs of rules and expectations that moderate non-'criminal' action in 'legitimate' business milieux and state practices. In short, the 'economic' that I support is not restricted to the financial domain, but presents exchange mechanisms as the modus operandi of social relations. Kidnapping is then the by-product, rather than the 'enemy' of social order, in our late modernity. The discursive relationship that legitimate apparatuses establish between it and 'organized crime' aims to consolidate their claim over the control of violence and to deprive kidnapping of its social identity. It is precisely the rationalized use of symbolic and physical forms of violence by the so-called 'criminals' that reinstates their identity as 'rebels' of the system—a system which is attacked from 'within', with the mobilization of its own weapons of forced and unequal redistribution of resources. To restate the title of the study, kidnappers capitalize on values at the expense of other people's lives and fortunes in a way as dangerous as it is politically ambivalent because of its 'entrepreneurial logic' that defines our late modern world.

Donia Smaali Bouhlila (2011) concluded a wide ranging study of the quality of secondary education in the Middle East and North Africa as follows:

Although, there are a number of reasons that lay behind this low performance, the most serious is that the native language of students is not that taught in school. The many dialects used may slow down students' performance. Arabic language will sound new for students in their first grade as it has not yet formed part of the spoken 'vocabulary'. From a policy perspective, it is complex to design an effective policy to overcome the difficulty of having to learn and read the school language since teachers most likely already use the spoken language to explain ideas and concepts. However, time devoted to teaching language must be increased. Moreover, the manner of teaching the language must be reconsidered….

Adrian Bell, Chris Brooks and Tom Markham (2013), reported a study exploring the performance of football managers. They concluded:

This paper has developed a new approach to measuring the extent to which the performance of EPL football club managers can be attributed to skill or luck when measured separately alongside the characteristics of the team. Following an approach outlined in the literature focusing on the mutual fund industry, we first used a specification that models managerial skill as a fixed effect and examines the relationship between the number of points earned in league matches and the club's wage bill, transfer spending and the extent to which they were hit by absent players through injuries, suspensions or unavailability. We then implemented a bootstrapping approach after the impact of the manager on team performance has been removed. This simulation generates a distribution of average points per match collected under the null hypothesis of no manager impact on performance. The actual average number of points captured by the manager was then compared with this distribution to ascertain the extent to which, after allowing for the resources at his disposal and other team characteristics, the club manager significantly outperformed or underperformed what would have been expected. We show that, unlike the fund management industry, the UK appears to have had a number of highly talented football managers whose success cannot be purely attributed to luck or the quality of their teams. On the other hand, there also existed managers whose performances were below expectations. We have evidence to support two key themes: first, that football club directors or owners who sack underperforming managers at a very early stage of their tenure sometimes make a decision supported by the bootstrapping model, if perhaps not for the correct reasons; and second, we can identify skilled football managers who, on occasion, are sacked for reasons that cannot be attributed to their on-the-field performance.

It may be that combining summary and conclusions results in a better less repetitive report; or recommendations may be a main feature and thus might be integrated into the conclusion.

Overall: It is extremely unlikely the first draft of the report will be the final one. This first draft will tend to include everything and be rather long. It is likely to be rather more descriptive than analytic. This is normal because it helps the researcher to create a cokmplete picture and make sense of what has been found out.

Treat the first draft as a discussion document and get other people to read and comment on it. Use whatever opportunity there is available to make a verbal presentation of the research in a small discussion group as this helps to sharpen the focus of the work. Do not be over critical of the writing in the first draft. Use this process to put words on the page and edit afterwards.

On the basis of discussions, comments and the researcher's own reflection on the first draft, produce the second draft of the report. This should refine the first version, cutting out repetition, making the report more analytic (that is, more focused on the aims of the research) and more structured. Again, get people to read and comment on this before producing the final product.

Produce the final version of the report. This should be the finished typed, error-free, well-presented version incorporating changes from the second (or subsequent) draft.

|